Welcome to Five Slices! I share five stories every week from science, art, psychology, culture, history, and business. To get it in your inbox:

The greatest footballer who never played football

Carlos Roposo alias “Kaiser” was one of the most popular footballers in Brazil for 20 years. He played for four clubs, attended every practice session, and hung out with his teammates. His entertaining stories kept the team’s morale up and he was a charming guy. But in all his time as a footballer, he never played a single match. If he had, the truth would have been revealed – that Kaiser wasn’t a real player.

Kaiser had a knack for finding journalists at parties and feeding them stories about his glorious past as a footballer. Then he would use their published articles to tell more elaborate stories to important people, and get signed on by clubs. After signing up, he always had an excuse to not play. During every training session, Kaiser would mysteriously get a “training injury” and back out of the next match – but he’d ensure his popularity by paying supporters to cheer his name from the stands. His teammates knew he was a joke, but they didn’t mind having him around because he was a jolly fellow. Team owners were more frustrated. They once even called in a witch doctor to try and break his streak of injuries, but Kaiser rejected him saying even black magic couldn’t solve his injuries.

Kaiser came very close to trouble when a gangster named Castro bought him for his team, and insisted he be sent in when the team was losing 2-0. Kaiser would fail whether he played or not – instead, he started a brawl in the crowd claiming someone had insulted him, and escaped in the commotion. It was open secret that Kaiser was a 171 (a fraud in Brazilian law). But nobody cared, because he was good at what he did and never got in anybody’s way.

Source: This is the original story in The Guardian1.

wrote an article about why people fake such elaborate stories in his article “The status cheats.” Great read, I recommend you check it out.

Mules

My friend and I were once standing outside a workshop waiting for a punctured tire to be repaired when a beggar approached us asking for alms. “No cash,” I muttered. “No problem, we have UPI!”2 they said whipping out a QR code which we scanned grudgingly. The payment was rejected due to “too many transactions” on the account. We were held hostage until we got some cash after which they vanished saying “Thank you for the consideration!” Something was shady about that bank account though. I wondered: How are these beggary networks structured? Who operates these bank accounts? How did they avoid taxation?

I think I might have solved the puzzle. The money was probably being moved through “mules.” Hawala networks were earlier used to move around unaccounted money. With payment systems moving online, “Mule-as-a-Service” (MaaS) networks are replacing hawala networks. Mules are middlemen between illicit businesses and their bank accounts. They operate through pyramid-shaped networks with levels:

At the top is the L3 “boss” who receives the money from illicit businesses, like illegal gambling sites offshore or phishing scams.

The L3 boss passes it on to multiple L2 “managers.”

The L2 managers recruit low-level L1 “employees” and distribute money to them. These L1 members either deposit it to a final account or withdraw the money.

The people at each stage get a cut (5-10%). The L1 and L2 folks are usually unwitting accomplices who want to earn part-time income. They are lured in with the promise of easy money (if people have sent you unsolicited texts on Telegram promising you money for very little work, you were probably being recruited as a mule). The regulators catch on eventually and block the accounts. By then, the ship has sailed.

Source: This story by The Ken (unfortunately paywalled)

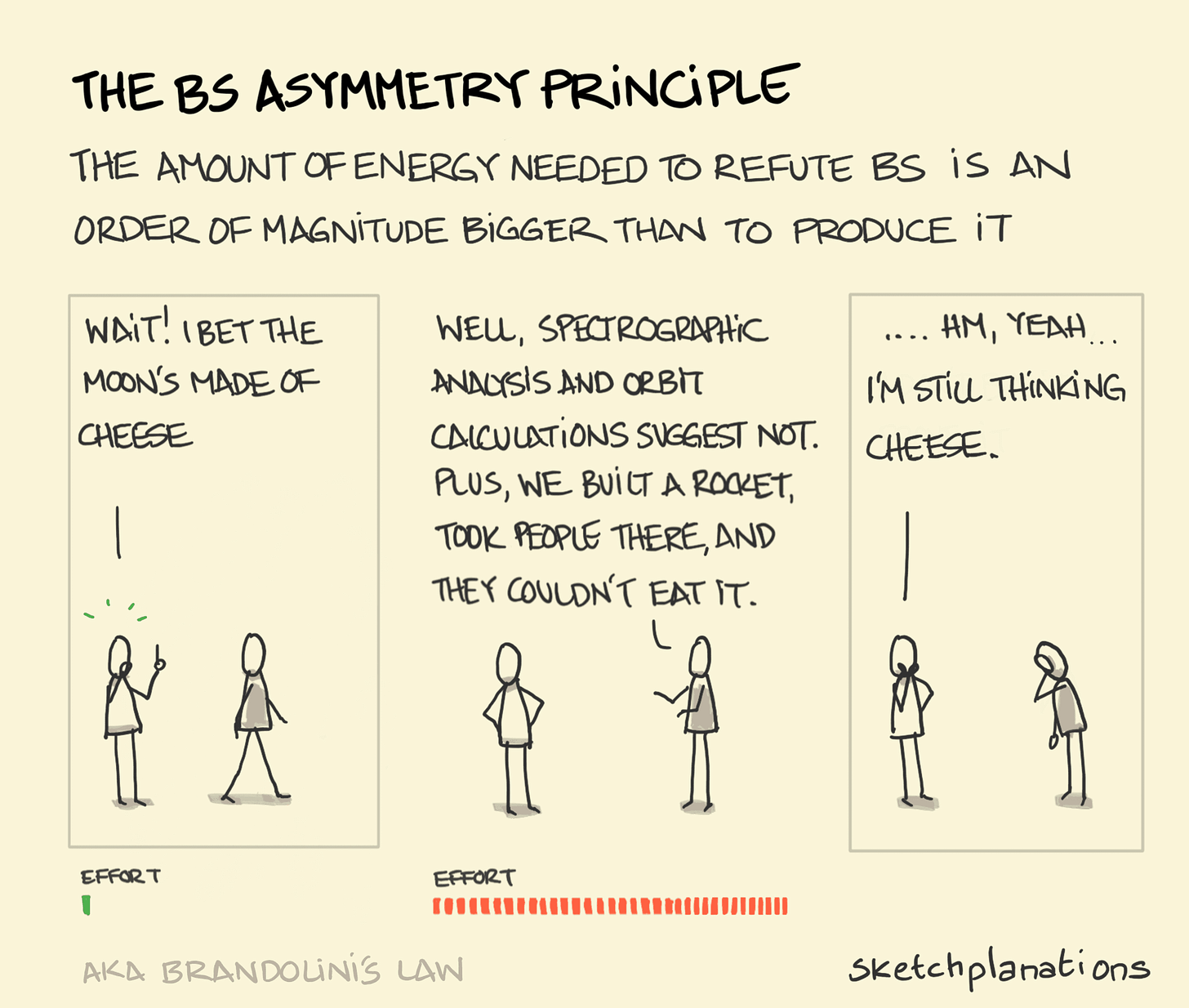

Why is it easier to start a scam than stop it?

“This one simple trick will let you live for a zillion years.”

”If you miss out on this cryptocurrency, you’re not gonna make it.”

”Millionaires don’t want you to know this.”

Tall claims like this on the internet aren’t very hard to spot. There’s a more insidious variety of this though – People with credentials, who look like somebody you can trust, whom you’ve followed for a very long time on YouTube or other social media, begin to promote questionable products, courses, or schemes.

It’s hard to resist the allure of these claims. We all want to get rich, healthy, popular, or happy. We secretly hope it’s true this time because this guy is more trustworthy than the previous one. And because it’s so hard to verify what’s going on, loss usually leads to self-blame. Journalists like Coffeezilla, Mike Winnet, and

have made it their project to dig deep into these stories and share the truth with the public. But this research comes at personal cost to the journalists.

Scott calls this Carney’s law: Sharing misinformation on the internet is much more lucrative than fighting it, because of the algorithms and institutions involved. The platforms have more to gain from the growth of entrepreneurial creators than from investigative journalists. The system is designed with that in mind.

Source: Scott Carney’s substack

The Salad Oil Scandal

In November 1963, two important things happened in America: John F Kennedy was assassinated. And Tino D’Angelis was caught. You need to know what Tino did, because it made somebody else a lot of money.

Tino started a company called Allied Crude Vegetable Oil through which he speculated on oil futures using soybean oil as collateral. However, Tino always claimed to have more oil than he actually did – most of the tanks in his warehouse were filled with water, and there was only a bit of oil floating on top. When inspectors would check the tanks, he would even shuttle the oil between tanks using an elaborate system of pipes (If Tino actually had the stocks he claimed to have, his warehouse would have had more oil than the entire stock available in the US). In 1963, he got caught and spent the next 9 years in jail.

This wasn’t Tino’s first caper. He had earlier sold US schools 2 million pounds of uninspected meat through a government program. He didn’t stop there. Three years after he was released from prison, he swindled livestock dealers out of $7 million worth of hogs, and was sent back to prison for another 7 years. After he was released in 1982, Tino again swindled $1 million (who’s letting this guy do business?), and went to prison in 1993 at the age of 77. He died at the age of 93 in 2009.

But something else happened in 1963: Tino’s oil stocks had received warehouse receipts from a subsidiary of American Express. When he was caught, Amex was on the hook for the loans they had made, and its share price collapsed. A well-known investor bought 20% of American Express for cheap, and it ended up becoming his best performing investment for a long time. That investor was Warren Buffett.

Source: The Salad Oil Scandal

The psychology of white-collar crime

Tino De Angelis is in the hall of fame of a long line of operators who were hailed as bold risk-takers or geniuses until they were caught doing something unethical, and then lost it all in a single day. Some other examples are:

Harshad Mehta, the trader who was worth thousands of crores until he was convicted of using forged Bank Receipts and market manipulation in the Indian financial market’s biggest scam to date.

Rajat Gupta, the managing director of McKinsey who was convicted and imprisoned for insider trading in the US.3

Bernie Madoff, a stock broker and market maker who ran a Ponzi scheme which lost thousands of people billions of dollars.

The Wolf of Wall Street, i.e Jordan Belfort, who pleaded guilty to market manipulation and to selling people worthless penny stocks.

These crimes are disturbing, yes, but what baffles me is why they did it. None of them actually needed the money. They had perfectly legitimate ways of earning income (Madoff was earning $550,000 per day). They were already worth billions, with a circle of people who respected them. So why did they risk it all on a side hustle?

A paper called “Doing a Madoff: The psychology of white-collar criminals” suggests a concept called the fraud triangle – the three factors of peer pressure (“everyone else is doing it”), opportunity (“maximize profit at all costs”), and rationalization (“no one’s getting hurt, and besides, the rules are different for me”4). When you inhabit a bubble in which your actions are far removed from your victims, you don’t feel the weight of your decisions as viscerally.

There might be a simpler explanation as well. As Morgan Housel writes in When Rich People Do Stupid Things, maybe these folks figured out everything in life except what “enough” means:

Kurt Vonnegut and novelist Joseph Heller are enjoying a party hosted by a billionaire hedge fund manager. Vonnegut points out that their wealthy host had made more money in one day than Heller ever made from his novel Catch-22. Heller responds: "Yes, but I have something he will never have: enough."

Share this with a friend who might enjoy it. Last week, I wrote about fantastic buildings and where to find them. You can find the complete list of posts here.

India’s peer-to-peer payment system, like Venmo

If you want to read Gupta’s side of the story,

has written a piece on it here. I find it hard to believe though.Which is basically how Crime and Punishment by Dostoevsky gets started…