Five Slices #30: Human-friendly design is when form fits context

Creating spaces and products with life in them

Welcome to Five Slices! I share five stories every week that show different angles of a simple idea. To get it in your inbox:

We’re about to hit 500 subscribers, so I launched a group chat. Click here to join. You’ll also get an email to guide you on how the chat works soon.

This week, I was watching a primer on Christopher Alexander’s work. He was an architect with a difference. When he designed buildings and spaces, he focused not just on how they looked or the purpose they served, but the possibilities they created — a building or a structure or anything that people interacted with wasn’t just an inanimate object, it was a living organism that shaped how people lived.

Look at these two buildings. The first one is a Soviet Era apartment, and the second one is a building designed by Christopher Alexander. Which one of these would you want to live in, and why?

If I’m guessing right, you would pick the second one. It just looks more inviting — it can be a community space or a place where you can sit by yourself, a place to play, to eat, to walk around… The function of the space adapts itself to your needs. The Soviet building guides your movements along a limited axis of functions, like factory items on a conveyor belt, but the second space gives you more degrees of freedom. More life.

Christopher Alexander’s principle was to look for fit between form (the thing being designed) and context (environment and constraints). This applies as much to architecture as to product design, communities, and a life that you enjoy.

If you want to watch the video, it’s here.

Today’s issue highlights examples of such human-friendly design in other areas of life. The other slices are:

The legendary inventor who obsessed over a vacuum cleaner

What Bell Labs and Pixar had in common

People who bring life to a boring party

Uber made waiting easier

The man who made 5,000 prototypes

This video has 1.6 million views. It’s an old man demoing a new kind of vacuum cleaner. What’s so cool about it?

The man is James Dyson, a legend in the product design space.

A common piece of advice to start-up founders is to solve your own problem. James Dyson took this maxim very seriously. He was frustrated with the vacuum cleaner at his house. He noticed that it lost suction power over repeated use, and taking it apart, he found that the fine dust particles were clogging the filters in the bag. Unless he made a “bagless” vacuum cleaner, the problem wouldn’t go away. But such a design didn’t exist in the market.

Dyson noticed that the sawmill near his house used a different method to clean out the dust particles called cyclonic separation. They rotated streams of air at high speed in spiral patterns. Heavy particles moved to the outer circles, hit the walls and fell into a removable collection bucket. Why not apply the same method to a vacuum cleaner? Dyson wanted to try this, but his company thought that a bigger company would already have done it if it was possible and that Dyson’s idea was crazy. They kicked him out of his own company.

Over the next 17 years, he tested over 5,000 prototypes to develop a perpetually high suction vacuum cleaner that didn’t need a bag. He took another 7 years to start his own manufacturing line — and he hasn’t stopped since. He went on to invent better hairdryers and bladeless fans. He’s worth $18 billion, and he’s still working on making a better vacuum cleaner. The latest demo video is for the lightest vacuum cleaner in the world weighing just 1.8kg and measuring 38 mm in diameter, and he’s added a new improvement to it so that hair doesn’t get stuck in the cleaner.

It’s really fun to watch him geek out on well-designed products like a pencil sharpener he bought in Japan that’s still working after 30 years. You can watch it here.

Pixar and Bell Labs

When the office for Pixar Animation Studio was being planned in 1999, the initial design was to have three separate buildings — for animators, for computer scientists, and for everyone else. Steve Jobs, who became CEO of Pixar around that time, thought this was a disastrous idea. He wanted people to have chance encounters and conversations. The space had to encourage people to get out of their office and mingle.

So the office was redesigned. At the center of the Pixar office is a large open space called The Atrium that everyone has to pass through. It has a reception, a cafe, foosball tables, a fitness center, and a theater. In Jobs’ original design, it also housed the campus’s only restrooms — this way, introverts were forced to talk to others at least when they were washing their hands. Looking at Pixar’s creative output since then, I’d say the plan worked.

Pixar wasn’t the first place to pull this off. Bell Labs in New Jersey was the breeding ground for so many inventions that shape our life today — transistors, cell phones, lasers, fiber optics, and some of the first programming languages — and it wasn’t accidental. Mervin Kelly, the chairman, designed the architecture of Bell Labs in a way that let researchers interact spontaneously. All scientists had to walk through a long corridor (that measured the length of two football fields) to get to the cafeteria, and it was inevitable that they would run into somebody and exchange ideas. They were also encouraged to work with their lab doors open so anybody could drop in at any time. That serendipity and collaboration created an idea factory that shaped the modern world with its inventions.

Source: Pixar office design, Bell Labs

The life of the party

How do you create a lively scene out of a bunch of bored people?

In Part 4, Chapter 9 of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, the most boring party in the world is taking place. People of different ages and classes, who have nothing in common, are all sitting together silently, wondering what to do. Then the host Stepan Oblonsky walks in. Stepan is a man with a talent for putting people at ease. He sees the situation and immediately gets to work.

On entering the drawing-room Stepan apologized, explaining that he had been detained by that prince, who was always the scapegoat for all his absences and unpunctualities, and in one moment he had made all the guests acquainted with each other. Bringing together Alexey and Sergey, he started them on a discussion of the Russification of Poland, into which they immediately plunged with Pestsov. Slapping Turovtsin on the shoulder, he whispered something comic in his ear, and set him down by his wife and the old prince. Then he told Kitty she was looking very pretty that evening, and presented Shtcherbatsky to Karenin. In a moment he had so kneaded together the social dough that the drawing-room became lively, and there was a merry buzz of voices.1

This paragraph was so relatable to me because I’ve seen it happen so many times in life. A fragmented scene becomes a hive of activity because of one person, not because they put themselves in the spotlight, but because they are able to make other people feel like they belong and start self-sustaining conversations. I don’t do this very well, but my dad has this talent, maybe because he grew up in a world where real-world interaction was a necessity and not an option.

What makes this possible?

First, it’s the ability to spot each person’s energy level.

Second, it’s the knack to match that energy level and make people feel seen.

But most importantly, I think it’s a willingness and courage to look embarrassed, and to start with just one person.

Most “scenes” need one person to take the initiative and at least one person to follow that energy. Watch this video on how one guy dancing becomes a movement:

Most times in life, we’re not trying to start a movement; we’re just trying to have a conversation with one or two people, and there’s a trick to being welcoming there, too.

has a great article called Good conversations have a lot of doorknobs and the principle is the same. It’s not about you being interesting, but giving the other person a “doorknob” to let them feel interesting. If they’re a good conversation partner, they’ll do the same and you’re off to the races. has a good article on this too, if you want to dig deeper.Waiting for an Uber

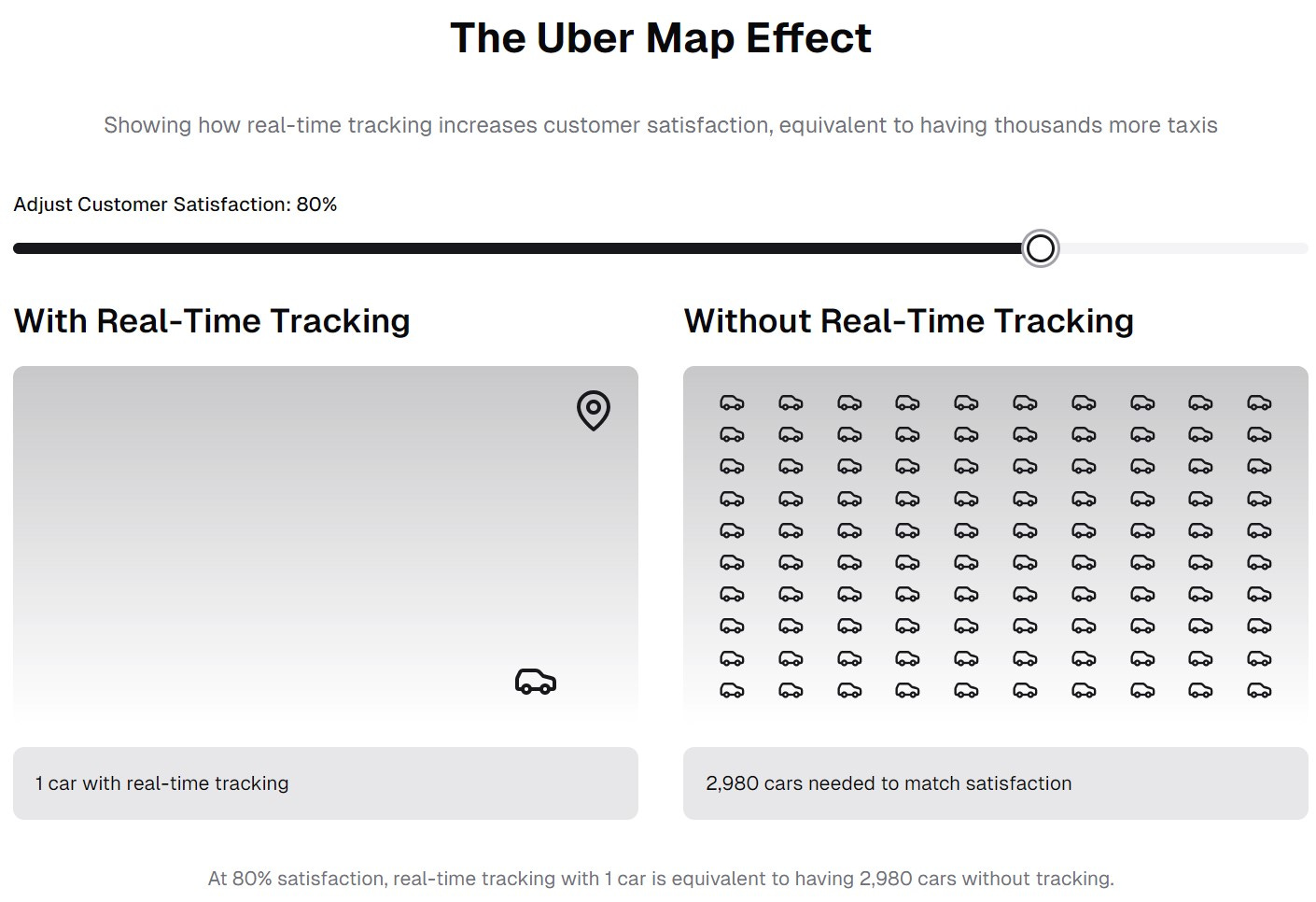

Uber didn’t reduce wait times. It just made the wait less frustrating.

Think about the last time you had to wait for a cab without using an app. You probably had to keep calling every 5 minutes to ask, “Are you there yet? Where are you?” Or it could be the other way around, maybe the cab arrived earlier than you expected, and he’s calling you repeatedly when you’re getting dressed or in the bathroom. How did Uber change this?

They gave a tracking mechanism that let riders know where the car was and how long it would take. It didn’t reduce the waiting time, but it reduced uncertainty and gave riders the feeling of control. A study highlighted that when people feel they have control over a situation, they feel less stress, even if there is no change in the outcome. That is what Uber did with “The Uber Map Effect.”2

So the next time somebody’s waiting for you, just letting them know you’re running late reduces the chances they’ll yell at you when you arrive.

Here’s another product idea: When you are driving a car, every minute of waiting time feels longer than moving time. This means that if a Google Maps route keeps you moving smoothly and even takes 10 minutes longer, it’ll feel much more peaceful than one that gets you there faster with more brakes and traffic stops. If someone makes a version of Google Maps that shows the smoother route compared to the faster route, I’ll buy it in a second.

Source: Rory Sutherland in his book Alchemy

Forward this to a friend who might enjoy it. Last week, I wrote about how ideas have a life of their own. You can find the complete list of posts here.

I have slightly modified this paragraph, sorry Tolstoy.

But there are other ways that ride-hailing apps can frustrate you. For example, cab drivers can keep canceling on you till you just go out and flag down one that won’t, which is what happened to me and my friend an hour ago.