Five Slices #7: The Japanese connection

The infinite library, folding spacecraft, stillness, Michelin star process, broken pots

Welcome to “Five Slices.” I’ll be sharing five stories and ideas from history, business, technology, culture, and art. Some will be fun, some will be useful, all will be interesting, and they’ll take you five minutes to read.

You can check out the complete list of posts here.

1. The complete library

Imagine you stumble upon a library that has every book in the world. It doesn’t have just all the books that exist, but all the books that ever existed and all the books that will exist. It contains your biography in hundreds of versions and parallel universes – as a short story, as a novel, as a hundred volume encyclopedia, written as a comedy, tragedy, adventure, or epic poem. It contains answers to questions you’ve always thought of, and questions to those answers. All the mysteries of the world have been solved and they are documented in this library.

Except, there’s just one problem. To find out what a book contains, you have to read it from cover to cover. There is no index or catalogue. The library has all the information you will ever need but no way to search for it.1 It’s like getting access to the internet albeit with no links between websites, let alone Google.

This is the premise of the short story “The Library of Babel” by Borges. It’s just eight pages long and it’s one of my favorite short stories ever.2 When I first read it, I was confronted by the finitude of my life and the impossibility of knowing everything there is to know, and it crushed me. But you don’t need to have an infinite library to disappoint you – reading all the books in a library or even a bookshelf is an impossibility, especially if you buy more books than you read.

The Japanese have a word for this: Tsundoku. It’s the habit of acquiring books and piling them up, without getting around to reading them. It’s nothing to feel guilty about though. Writer Umberto Eco assembled an “anti-library” of 50,000 books that he never intended to complete – like a set of healthy snacks to choose from, the library was aspirational and a place to go to for research, a reflection of what he wanted to read. A library is not a to-do list. Don’t pressure yourself to complete it.

2. Paper folding spacecraft

Robert Lang has a Master’s in Electrical Engineering from Stanford and a Ph.D in applied physics from CalTech. He has worked on over 80 publications on semiconductor lasers, optics, and integrated optoelectronics, and holds 46 patents. In 1988, he started working for NASA’s Jet Propulsion laboratory.

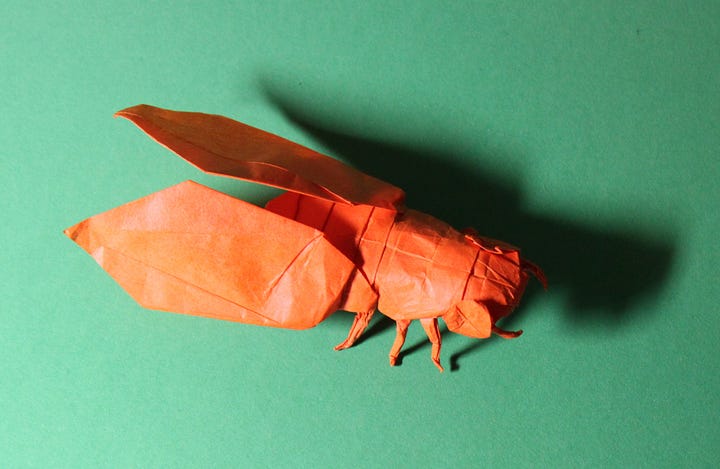

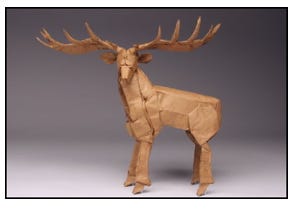

But Lang is most famous for something totally different – origami, the Japanese art of paper folding. In 2001, Lang quit his job to pursue origami full-time.

Lang had been folding paper designs since his childhood into patterns like these:

Over the years, Lang was able to meet and learn from a number of other Origami artists from both America and Japan. He also started experimenting with the intersection between mathematics and origami by writing computer programs that helped him with designing more efficient folding patterns. One place this came in handy was at his work with NASA – long-distance space journeys are powered by massive solar sails, but these sails have to fold and expand at different stages. Lang’s origami designs helped save a lot of space and money.

If you worry about how a career move will look on your resume, remember that this man went from Jet Propulsion scientist to origami consultant.

3. The art of stillness

One bit of advice to writers is that everything you write must either build character or advance plot. But one of my favorite bits of writing is from Murakami’s first book, Hear the wind sing where the protagonist does nothing:

There were two well-tanned girls on the tennis court, hitting the ball back and forth, wearing their white hats and sunglasses. The rays of the sun bringing the afternoon suddenly increased in intensity, and as they swung their rackets, their sweat flew out onto the court. After watching them for five minutes, I went back to my car, put down my seat, and closed my eyes and listened to the sound of the waves mixing with the sound of the ball being hit.

The scent of the sea and the burning asphalt being carried on the southerly wind made me think of summers past. The warmth of a girl's skin, old rock n' roll, button-down shirts right out of the wash, the smell of cigarettes smoked in the pool locker room, faint premonitions, everyone's sweet, limitless summer dreams. And then one year (when was it?), those dreams didn't come back.

Nothing much happens in this scene, but it’s an image, a moment to catch your breath before you move on. Such moments of stillness seem to be a unique feature of Japanese culture – they even have a name for it, ma, or the negative space which contrasts with the content. The shadows are as important as the light, the silence in the music complements the notes, and an empty page presents the most possibilities.

Here’s a video on how Studio Ghibli movies make the most of this concept:

4. Michelin Star Process

I’ve been watching the TV series, “The Bear.” In this, Carmen, a world-class chef comes home to save and revamp his brother’s failing sandwich shop. It’s an intense watch. Carmen is a misfit, insisting the cooks “sharpen their knives” and “clean their stations.” He organizes his rustic team into a French Brigade. He addresses brawny cooks as “chef.” Initially he is mocked for using elite processes in a rundown kitchen.

But then something funny starts to happen: When Carmen treats his workers like elite performers, they begin to believe it themselves, and they raise their game. It’s similar to Steve Jobs’s “Reality Distortion Field.” But while Jobs pushed people to achieve extraordinary results by using the anxiety of an impossible goal, The Bear is more about designing a new normal. If the daily process improves, the results will come.

It’s more like the Japanese process of Kaizen (continuous improvement). By improving 1% every day, you’ll end up 37 times better in a year. 1% isn’t much. But it adds up.

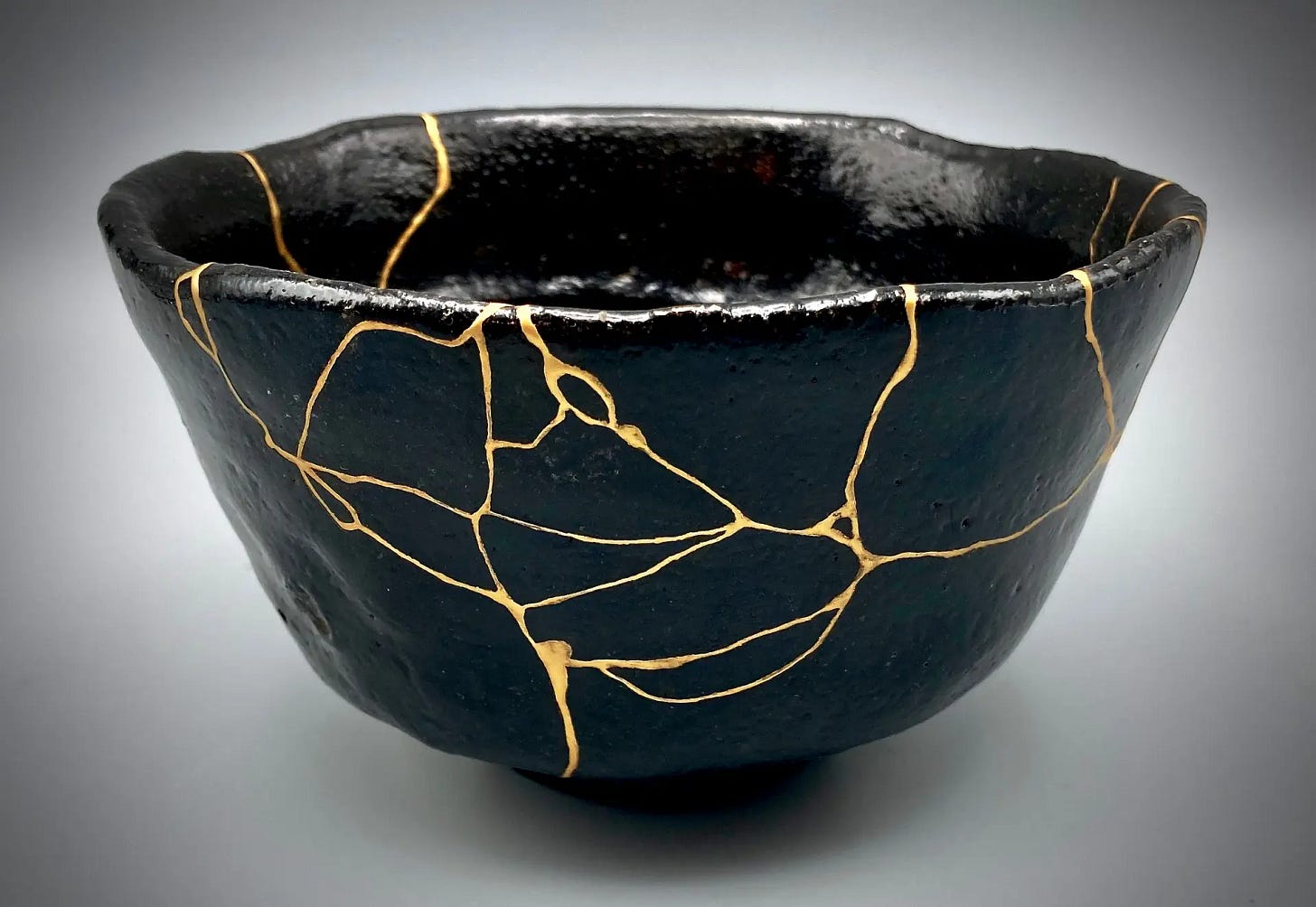

5. The beauty of broken things

If you break a ceramic pot, you can either throw it away or attempt to hide the damage by gluing it back perfectly. There’s a third option though: To highlight the damage by using golden lacquer so that the cracks are fully visible as part of the design. This is called Kintsugi or “golden repair”.

Kintsugi is an extension of the Japanese philosophy of Wabi-Sabi. It advocates embracing the flawed and imperfect parts of life instead of hiding them. Wear-and-tear are aesthetically valued as marks of service, and there is an acceptance of the transient nature of things, appreciating all stages of an object’s lifecycle.

Not only is there no attempt to hide the damage, but the repair is literally illuminated... 3

If you tend to be hard on yourself, Wabi-Sabi is something you could try not just with broken objects but with your own life.

If you enjoyed that, you’ll love my post Time Games and my other post on Anthony Bourdain’s worst job interview. If you want to read something longer, check out my experience cloning a billion dollar company.

To support my work, please like and share this with a friend:

The worse part is that the library contains all possible books, most books in the library will just be random gibberish. Finding even an intelligible book is a hard task in the library. But you have an eternity to keep searching… All the best.

If you’re familiar with “The Library of Babel,” check out the infinite monkey theorem and “The Total Library”, Borges’s essay on the origins of the story.

Sort of like Eminem from the last song in 8 Mile (WARNING: Explicit lyrics and a lot of swearing).